Godfather Pacino (Late 60s - Late 70s/Early 80s):

Al Pacino is one of the most famed and critically acclaimed actors alive today. His status as one of the most serious greats began relatively early in his career, when, in 1972, he stared as Michael Corleone in Francis Ford Coppola’s mafia masterpiece The Godfather - a film that needs no introduction.

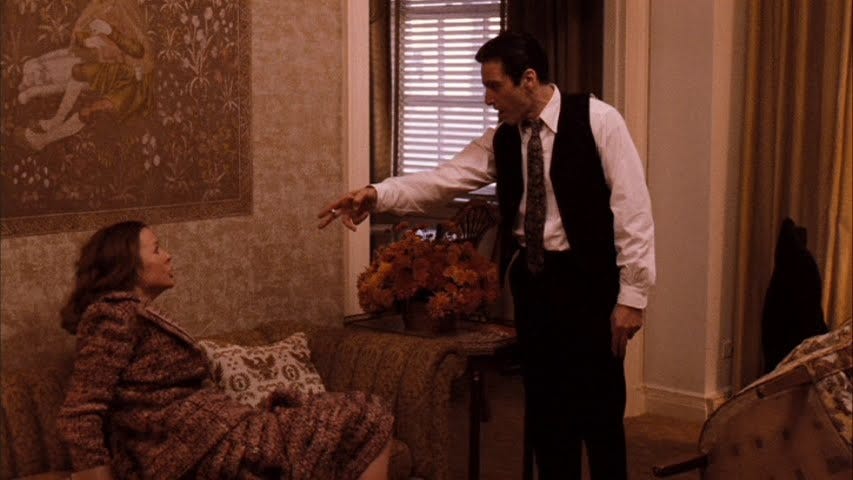

Michael Corleone is a character study of a deeply conflicted man, who’s love for his family is matched by, precluded in fact, by what is discovered to be an immense capacity for violence. He is cold and calculating, and when he loses its cool - such as in Godfather II when he hits his wife Kay (Diane Keaton) because she had an abortion - its anything but funny.

Actually its terrifying. When Michael Corleone is upset, his response is not one of rhetoric, but of violence. Indeed, one of the most interesting and disturbing elements of the film is Michael’s exploration of his own capacity for violence, its development over the course of the story in response to very real threats, and the creeping suspicion (among the viewer, the character, and even Michael himself) in the course of his descent, that there may be no bottom at all to the abyss that is the human psyche1.

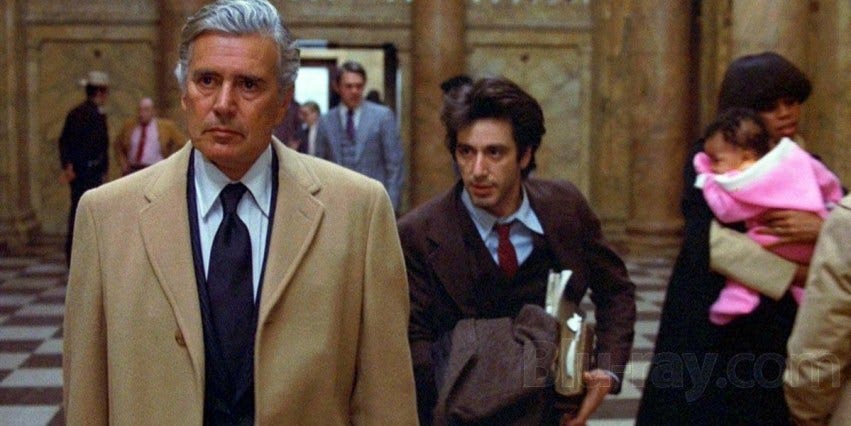

Pacino’s other early roles, such as in Serpico (1973) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975) - both gritty, crime/drama films - are very similar (though not as masterfully constructed) in terms of characterization, in which Pacino portrays apparently subdued but unstable figures (heroes or villains) who’s internal contradictions threaten to break through the surface and erupt in violence at any moment.

The New Pacino (Early/Mid 80s - Present):

However, at some point, Pacino’s style of underwent a gradual but dramatic shift. 1990s Pacino and 1970s Pacino are unrecognizable to the point that many who have seen both Michael Corleone and Richard Roma (a more recent Pacino character), may fail to realize that both characters are in fact portrayed by the same person.

This confusion is in no way helped by visual appearance. Pacino’s stylistic shift also seems to have manifested physically. There noticeable physiological differences between Godfather-era and mature-era Pacino that seem to allude the process of aging.

The new Pacino seems gaunt, his face shrunken ever so slightly, yet what is most noticeable is a spryness of body, signaling a greater tilt towards the hyperactive. In the decades that followed this tectonic shift, his appearance would take on ever stranger forms, more alien to the man or actor he once was.

The conspiracy-minded may come to the conclusion that the deep state replaced the original Al with an animatronic body double. But if this were the case, surely they could have done a better job2.

And whereas the old Pacino was dark, brooding, a man of few words the new Pacino is defined by his over-the-top, sometimes zany characterization. If the old Pacino was memorable for what was simmering underneath, the new Pacino is a man of deafening, anger-filled, ranting outbursts, overacting, and idiosyncratically bizarre speech patterns.

This Pacino is an entirely different animal.

The shift is especially visible in the crime/drama film Heat (1995), which is somewhat similar in terms of tone and story to the type of film Pacino may have starred in earlier in his career. However, the Pacino we get in Heat is far from the old Pacino. In Heat, Pacino plays a veteran police detective forced to reckon daily with the dark side of humanity and the detrimental effects of this ‘double life’ on his marriage.

This, however, does not prevent Pacino from treating the audience to some serious laugh-out-loud moments. For example, when Pacino meets with an informant, he jives at him, shakes the table, even starts to sing at one point, before punctuating the scene with the (in)famous line:

Perhaps more memorable though is when Pacino is interrogating a man having an affair with a suspect’s (Val Kilmer’s) wife, raising his voice unprompted and telling him that “SHE’S GOT A GREAT ASS!”. Staring opposite to Robert de Niro, who’s style (unlike Pacino’s) has stayed relatively consistent since the beginning of his career in the early 70s, making Pacino’s outlandishness all the more jarring.

Pacino has also acted in several film adaptations of plays, where there is typically far less room in the script for these types of crazy, scenery chewing moments3. Yet Pacino’s shtick will easily shine through even the most venerable source material. In a 2004 adaptation of Shakespere’s Merchant of Venice (2004), Shylock, the play’s memorable antagonist, undergoes a thorough Pacinoization. If the Bard of Avon (let alone the director) can not fully reign him in, then who can? Still, its a great performance.

Meanwhile, in Glengarry Glen Ross (1992), an adaptation of the 1969 David Mamet play of the same name, becomes the vessel for some of Pacino’s most memorable and outrageous tirades4. The inexperienced manager John Williamson (Kevin Spacey) unwittingly scares off one of Richard Roma’s (Al Pacino) clients moments before closing a sale. Although it lasts less than two minutes, an enraged Pacino rips in to Spacey with a maniacal brutality that I have yet to see captured in the medium of film, unleashing a deluge of verbal abuse that seems to foreshadow the disgraced House of Cards actor’s #MeToo era demise.

By the late 90s/early 2000s, Pacino’s shtick had reached absurd levels. In Devil’s Advocate (1997), Pacino portrays the titular fallen angel starring opposite to Keanu Reeves. Needless to say, it is difficult to take this film seriously, a feeling helped in no small part by Pacino’s shark-jumpingly, CGI-fueled, positively zany performance. One critic described it as having “a nearly operatic sense of absurdity and excess”5, yet it is difficult to imagine that the ‘absurdity’ of the finished product bore any resemblance original concept; that is, before Al Pacino walked on set.

However, perhaps even more foreboding than this Fausto-Miltonian tale of decline and temptation was his involvement with the infamously horrific Adam Sandler comedy/disaster film Jack and Jill (2011). Pacino’s involvement could be conclusively described as a low point in his career, a nadir comparable in terms of magnitude only by the astronomical heights of his Godfather-fueled stardom - just as the evil one, the prince of darkness once enjoyed the greatest heavenly favor before his fall from grace into the deepest, darkest reaches of the abyss. Likewise, in the most infamous scene, Pacino dances, sings, and even raps in a Dunkin’ Donuts™ commercial.

Thus it is fitting that in Jack and Jill, Pacino (who is playing himself) invites the clumsy, accident-prone Jill (Adam Sandler in drag) to his house to bed her, where she accidentally clubs his Oscar statuette, breaking it into a million pieces. How can any man become such a parody of himself?

What was he thinking? But more importantly, how did this happen? To attempt to explain either would require access to the inner-working of Al Pacino’s mind. A Pacinology based on anything less would be mere speculation. However, while the how is beyond our reach, I do believe it is possible to pinpoint the when, which in turn may provide us with a certain level of insight.

And in the case of any artist, the periodization made possible by creative output can help us learn about them as both a person and as an artist. And because Pacino is an film actor, working not behind the scenes but as the main attraction and subject of the viewers attention, we are given ready access to his person because he is the performance.

First of all, by the early 90s, audiences and critics had clearly began to pick up on Al’s hamminess, which by that point had become impossible to ignore. In Scent of a Woman (1992), Pacino plays Slade, a blind, crass, ill-tempered but good-hearted veteran who takes a young man under his wing, takes him to New York, and shows him the high life.

In what had already become a hallmark of the Pacino format, the climax of the film famously involves Pacino unleashing a irreverent, bombastic, and profanity-laden tirade in an unjust judicial setting - in which he may or may not be told that he is “out of order” by the hypocritical powers that be6. As we will see, the special power of Pacino’s shtick in these type of oratory courtroom scenes may be no accident.

Although the film in general and his performance in particular received flattering reviews, the picture of Pacino painted by critics is certainly not Godfather Pacino. Janet Maslin in her interesting, carefully-worded New York Times review wrote that “Mr. Pacino has a way of explosively dispelling any doubt. From the moment he first appears, sitting in a darkened room blasting insults at the hapless Charlie, he seems to take up all the story’s dramatic space”7.

This statement is also useful because I believe it perfectly articulates what the new Pacino is all about. We can use it as a litmus test, Pacinometer, if you will, because while it was originally intended to describe his performance as Colonel Slade, the same could easily be said of Richard Roma, Vincent Hannah, and any of the other notable modern Pacino characters.

This statement clearly does not apply to Michael Corleone in Godfather Part I and Godfather Part II. In Godfather Part III (1990) - easily considered the weakest of the three - Coppola (having had to deal with the likes of Marlon Brando) was mostly able to keep his performance under control, though there are moments when the mask begins to slip. He also speaks (and shouts) like the new Pacino.

The Theory of Alvelution (Late 70s - Mid 80s):

A lot of people may be tempted to associate Scarface (1983) with Pacino’s phase change. After all, Scarface and it’s titular macho drug kingpin Tony Montana (Pacino) is all about money, machine guns, speedboats, mountains of cocaine, and the state of Florida - none of which are noted for their subtlety.

It is also seemingly true that in Scarface Pacino greatly expanded upon his range as an actor and experimented with the bag of tricks that would characterize the late-stage Pacino. The screaming, the outbursts - all of that can be found in spades.

Yet I would argue that Scarface is not a good place to put the boundary because Tony Montana is not a true Pacino character. What I mean by this is that, in Scarface, Al Pacino is a vehicle for the character of Tony Montana, whereas, in Glengarry for example, a character like Richard Roma is a vehicle for the character of Al Pacino. The fact that Pacino is able to reach the level of characterization that he does in Scarface can only be a testament to his skill and range as an actor, but besides that Scarface gives us little information about the man himself.

In any case Scarface represents such a dramatic departure from Pacino’s shtick (both old and new) that it is difficult to compare it with any point in his career before or since. But if I had to venture a guess, my gut (and my eardrums) would tell me that Scarface has to be new-era Al Pacino disguised by several layers of Cuban make up.

Regardless, there are far better options.

The Missing Link (Late 70s - Early 80s):

I would argue that we really begin to see the new Al come out at some point between the late 70s and early 80s. During this time, Pacino was involved with a series of really interesting projects, gritty, smaller in scale that even some of his early 70s roles like Godfather and even Serpico but similar in their gritty atmosphere and the anti-heroic of its characterization. They’re all great in their own way, though theres always the lingering question of why a post-Godfather Pacino would have taken them on in the first place.

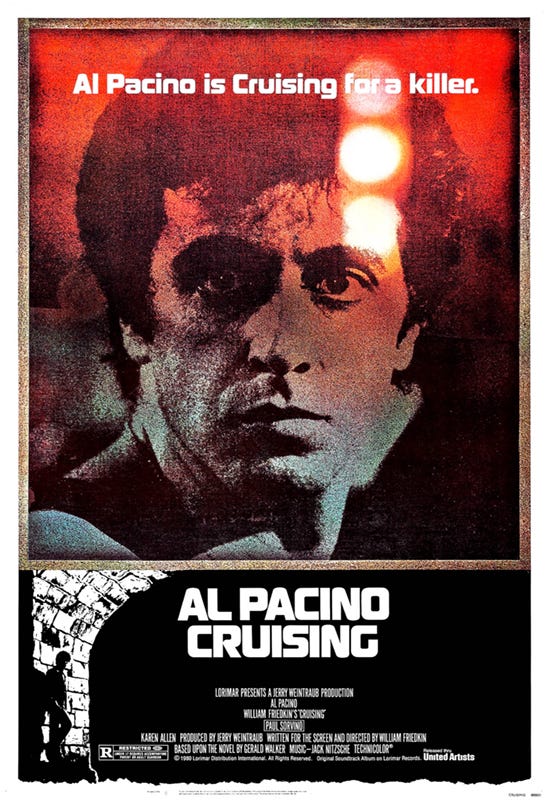

Take Cruising (1980) for example, directed by the visionary filmaker William Friedkin, who terrified an entire generation with The Exorcist (1973) before evolving into more subtle projects like Sorcerer (1977) and, more importantly for the sake of this discussion, Cruising (1980). Despite what today can seem like a slightly dated, silly concept, Cruising is a terrifying film and an incredibly effective police/crime thriller. Still, it was an incredibly odd project for Pacino to take on, not to mention a risky one carrer-wise.

In Cruising, Pacino plays an undercover cop on a mission to infiltrate the hardcore gay scene amidst the urban and moral decay of 70s/80s New York. That is because there is a silent, sadistic killer praying on gay men - what would prove to be a tragically prophetic concept. In order to find the killer, Pacino must fully immerse himself in the gay community - all the way - even though, at least according to Oliver Stone’s bizarre JFK movie, they might have killed Kennedy8.

In any case, there are several scenes in Cruising that could have or might have broke Pacino. One notable scene sees Pacino going to an underground BDSM party, sniffing a popper-soaked rag, and dancing erratically. In another scene, Pacino, clad in full denim, is taught the ins and outs of the bandana system. Pacino opts for the yellow one. Talk about method acting!

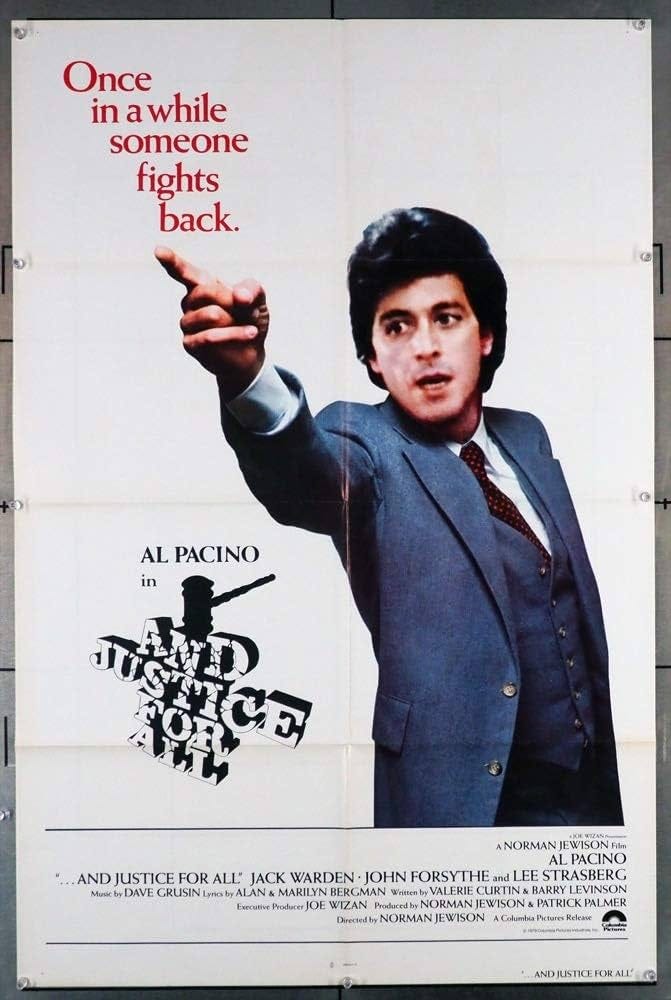

…And Justice for All! (1979):

In this underrated legal drama/black comedy, Al Pacino plays an idealistic but exhausted public defender blackmailed into representing Judge Fleming, a notoriously cruel and corrupt judge charged with committing a violent rape. It is here where I would argue the new Pacino emerges from the old. Let’s consider the film in close detail so we can get a good sense of Pacino’s characterization.

Its also a great movie for all my Baltimore people out there… hun!

In many ways, Justice has a lot in common with the new Pacino himself and the type of projects he typically chooses. Pacino’s shtick aside, later films like Glengarry and Heat do not make for light viewing. Pacino has never been a comic actor, even if his antics . And Justice presents us a very serious critique of the American justice system, its inefficiencies, and its inequalities. The picture it paints is bleakly grotesque, almost Dickensian. Yet like a Charles Dickens novel, there is a very strong undercurrent of the ridiculous.

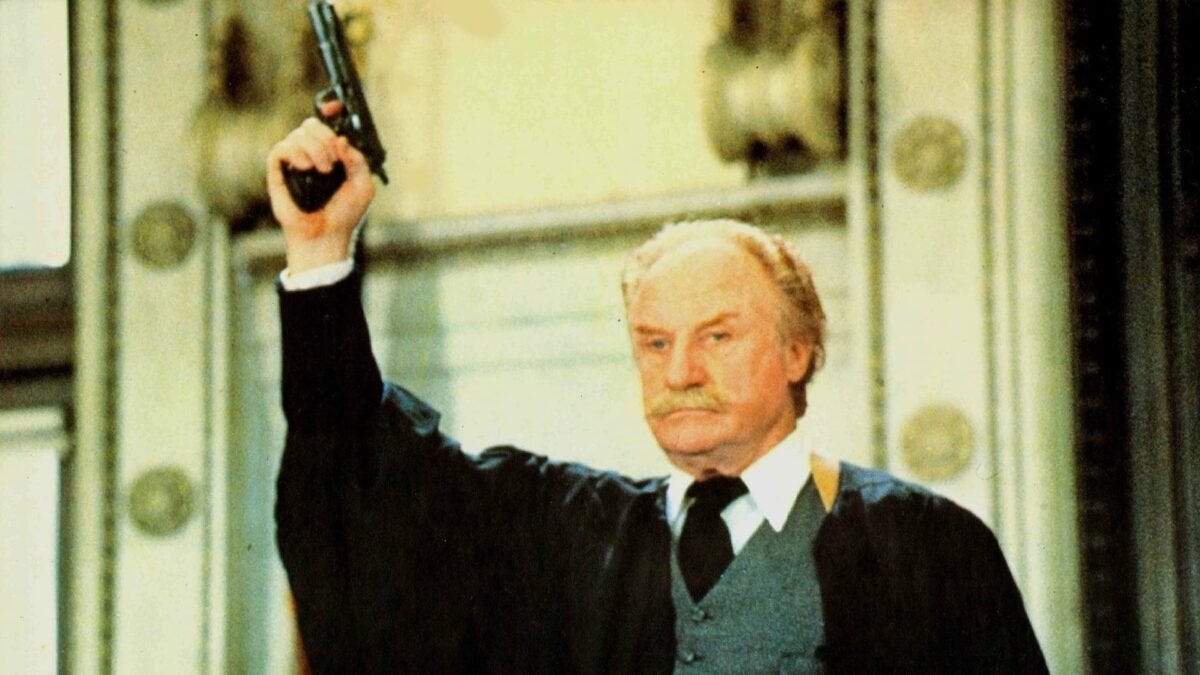

For example, Arthur Kirkland (Al Pacino) is close friends with a the reckless Judge Rayford (Jack Warden), a reoccurring comic relief character whose thrill seeking behavior, which initially comes off as amusing, becomes increasingly disturbing, self destructive, even suicidal as the film progresses9.

This type of thematic progression (decalage) - droll when we first see it then depressing when the viewer realizes its implications and consequence - is present in every facet of justice, of injustice, which that the characters are forced to reckon with in different ways. Fittingly, the central axle of this overarching feeling is our protagonist, Arthur Kirkland, played by Al Pacino.

For most of the film, certainly in the first two acts, Kirkland’s character is pretty. typical old-school Pacino. Idealistic but grounded, high-minded but pragmatic, Kirkland represents a small light of humanity in what is an otherwise in-human system. Pacino is trying his hardest, but as is the case with public defenders, he is exhausted, underpaid, overextended, and is confronted with indifference at every turn10.

We are made familiar with Kirkland’s clients. Jeff (Thomas Waites), a young man was sent to jail over a broken tail light, falsely accused of a crime in another state, exonerated but sent to jail anyway by Judge Fleming because of a minor technicality. But we also hear about the opposite scenario - the law and order counterargument - a case where an old woman was killed during a botched robbery but the clearly guilty defendant receives only a year of probation. Nothing works as it should.

Mercy is a scarce resource, doled out only to the least deserving - the benefit of the doubt is granted only to the worst actors. When Kirkland tries to appeal to Judge Fleming (Henry Forsythe), he is rebuffed out of spite. When it is revealed that Fleming himself his been arrested and charged with committing a violent rape, Kirkland along with fellow public defenders Porter (Jeffery Tambor11) and Fresnell (Larry Bryggman) take great satisfaction in the irony.

But then they reveal something else: Fleming has requested Kirkland to defend him in court. Kirkland looses his steely, reserved, old Pacino demeanor and breaks into maniacal laughter - a scene of critical importance to the plot of the film, but also to Pacino’s development as an actor. Look closely:

Yet like the rest of the film’s comedic elements, the audience is given little time to take comfort in this irony as it is undercut by the depressing logic at work behind the scenes. Fleming has requested Kirkland, who is known as an honest and sincere defender of the innocent, as a cynical ploy to garner sympathy. Although Kirkland is has understandably very little sympathy for Fleming, he has little choice in the matter - if he refuses to take on the case, Fleming’s powerful friends will conspire to have him disbarred.

He reluctantly agrees, noticing that unlike most of his clients, Fleming receives every conceivable official and unofficial form of protection the system has to offer, hoping that this may be extended to his own clients in return. After all, lawyers cut deals all the time. In Justice, this type of quid-pro-quo rationalization is taking place on every level, regardless of its shaky foundation.

As the plot unfolds, a creeping sense of disillusionment and alienation begins to wear on Kirkland and the people in his life. An increasingly pessimistic Kirkland and his girlfriend Gail Packer (Christine Lathi), who works on the court’s judicial review board, get into increasingly frequent arguments as Kirkland remains critical of the project, deeply skeptical of the legal system’s ability to reform itself. They make up, but the tension is palpable in every scene between them.

Later that night, Porter barges into Kirkland’s apartment drunk. Initially, he seems celebratory, telling Kirkland that he managed to get a client’s murder charge thrown out over a technicality. Then he reveals that only hours after his release his client was arrested again for the murder two children. Pacino attempts to reassure him, reminding him of an attorney’s obligation to defend their client to the best of their ability, but this is little consolation.

We are at least given some relieve in Fleming case, as Pacino learns that the judge agreed to do a polygraph test after initially refusing and passed; leading Kirkland to start believing Fleming’s claims of innocence - laying the groundwork for what would appear to be a predictable reconciliation between the two.

Over the next few days, Porter begins acting erratically, shaving his head, and making cryptic comments. While Kirkland tries to explain is actions and insists that “he’ll be ok”, Gail begins to question his fitness as an attorney, leading to another argument. But at the courthouse, Porter suffers a violent mental break.

Kirkland needs to be in court later that day for the probationary hearing of one of his client, Ralph (Robert Christian), an eccentric but sympathetically portrayed cross dresser. Kirkland accompanie Porter to the hospital, begging Fresnell to attend the hearing in his place and submit his revisions to the probation report so his client can avoid jail time.

Schmoozing at a fancy restaurant Fresnell loses track of time, shows up late to the hearing, and forgets to submit the revisions - leading to a harrowing scene in which Ralph is denied probation and sentenced to jail. Later, the jail informs Pacino that Ralph hanged himself in despair.

The leads to what is probably the first real, serious Pacino rant of all time - what would grow to become the bread and butter of his dramatic arsenal. Unlike certain new era Pacino outbursts, this confrontation is neither entertaining nor out of place. It may be in a sense cathartic, but it is anything but comedic and far from satisfying. Still, it’s a Pacino rant through and through, and a damn good one at that:

This is where things start to go downhill for Kirkland. Despite Fleming’s promises, little is done to help Jeff, whose mental and physical condition continues to deteriorate. Eventually, he snaps and steals a guard’s gun, leading to a hostage situation. Kirkland goes to the jail to try to talk him down, where we learn the depths of his desperation. Jeff walks in front of a window and is killed by a police sniper.

Kirkland’s grandfather Sam (Lee Strasberg12), who inspired him to become a lawyer and is the only member of his family he keeps in regular contact with, continues to spiral deep into dementia. Kirkland typically visits him every week, but work has kept him away, causing Sam to loose his perception of time and further deteriorate.

Then, Carl (Dominic Chianese13) one of Kirkland’s shadier clients comes by his house with a lady of the night in tow. In Carl’s car, the woman shows him illicit photographs of Fleming engaged in some BDSM, reigniting Kirkland’s suspicions that he may be guilty after all.

When he confronts Fleming with the photographs, the judge tells him point blank that he did it, adding that the polygraph was results were rigged, something that his powerful friends “took care of” for him. In a later scene at his large country house, Fleming tells Kirland that “the idea of punishment to fit the crime dosen’t work, we need unjust punishment”. Kirkland leaves in disgust and grows increasingly depressed.

This leads us to the film’s climax - Judge Fleming’s day in court. Kirkland begins his opening statement - a smooth piece of lawyerly equivocation if ever there was one spoken directly to the jury. He makes a very convincing argument. Even Fleming looks on in approval. Everything is going to plan. That is, until this happens:

I rest my case.

Pablo Pacino:

But there is one more thing that I’d like to mention. While it may appear that this piece was largely written at Mr. Pacino’s expense, this could not be further from the truth. Rather than disparage or deride, my sincere and consistent intention throughout has been to celebrate his career and his incredibly unique, if not singular evolution as an actor.

By the way, in each of the films I have mentioned up to this point, Pacino’s performances are easily the best thing about them (with the exception only of Godfather I because of Marlon Brando). You can tell he’s having fun with it. One way or the other, Pacino steals the show because he’s great at what he does.

And to say that the new Pacino is different from the old Pacino is not at all to say that one is better than the other - though I’m sure that plenty of snobs feel that way. Of course people are entitled to make aesthetic judgements as they see fit, but the critic should take care not to fall into the trap of misunderstanding the artist’s intentions.

Creative evolution never occurs in a vacuum. Art’s don’t change their style just for the all of it. Cubism, for example, gave artists like Picasso avenues to express themselves in ways that were simply not possible even in the newer, more abstract schools such as Impression. Cubism, among other things, allowed artists to produce an image of the same subject from the perspective of several different positions simultaneously.

Critics were not wrong when they said there was something unmistakably bizarre in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Picasso’s first major Cubist undertaking. But to argue that this causes it to fail as a work of art would be to miss the point entirely.

Likewise, there is something characteristically bizarre in the outlandish expressionism of Pacino’s shtick, but it would be wrong to say that Pacino’s performance in Heat fails as a performance and simply leave it at that. Obviously, everyone is entitled to their own aesthetic judgements, but you can not deny that both Picasso and Pacino are effective as artists - regardless of how you think it looks.

A common recourse for critics of modernism is that modern artists act in bad faith. To say that Demoiselles appears the way it does because Picasso was simply too lazy to finish the piece would be one such example - which was a very common criticism of the painting when it was first received. To dismiss Al Pacino’s weirdness as just ‘phoning it in’ would be another.

Although this type of criticism is often rooted in a severe deficiency of imagination, these suspicions are not without their merit. As mentioned in my previous article on Bad Art, every artistic discipline - from painting to acting - has its hacks.

But you know what hacks almost never do? Take risks. I would argue that if there is one thing that every hack has in common, it’s risk aversion. Hacks are notoriously risk averse. A comedian who doesn’t change his material in 40 years is a hack, while a good comedian never tells the same joke twice14. To do so requires not only skill, but confidence - not merely in one’s own abilities, but rather in the conviction that one’s past, present, and future successes are not the result of accident15.

And who could accuse Al Pacino of lacking in confidence? Especially this type of confidence? The success of The Godfather elevated him to the heights of popular and critical acclaim. It would have been really easy for him to rest on his laurels and play it safe. Say what you want, but Pacino’s shift in style is not exactly what I would call playing it safe. Nor are his performances themselves - highly energetic, expressive, and instantly engaging - what I would call ‘phoning it in’. ‘Phoning it in’ implies an actor living on his name brand, taking a role for a quick buck, and applying minimal effort in the performance.

But if Al were phoning it in, he wouldn’t be having so much fun.

For Al to adopt that level of expressionism, to undergo such a radical transformation at that point in his career is understandably a difficult thing for most people to wrap their heads around. But one must understand that to make great art means rolling the dice. If it fails, so be it, but you can’t say this has ever stopped him. The mature Al Pacino is not only unafraid of these risks, but obviously takes great enjoyment in taking them - he gets off on it.

There are few hats that Pacino hasn’t worn, Pacino has always been seeking out new things, unexplored avenues of expression. To quote Tyler “Mr. Movies” Palicia, a noted authority: “He’s played gay, he’s played blind, and he even played Cuban. But he never played fat, and I think that was a loss for the culture”. This can only lead me to one conclusion, that Al Pacino is not only great at what he does, but he also has a deep love for the craft.

And at the end of the day, isn’t that what being an artist is all about?

It is no surprise then that the violence originally employed to protect his family is deployed against them as soon as they begin to seriously defy him or pose a threat his plans. Those who become dependent on violence as a recourse to their problems will find out sooner or later that violence, when set free from its box, will resist control.

“Cry havoc, and let slip the dogs of war!”, says Marc Antony in Julius Caesar, a line once delivered by a young Marlon Brando. Central to the drama of both works is the ambiguous nature of violence and its tendency to transform from a means to an end to an end in itself. And by the end Godfather II, violence is the only language Michael understands.

In film at least, the old Pacino speaks in a general American East Coast accent. However, this has been replaced by what I can only describe as a curious linguistic mélange of perfect American English pronunciation offset by a distinctly Italian use of diction, emphasis, enunciation, etc. While Pacino of course is of Sicilian heritage, I have yet to hear an Italian-American accent remotely similar to his.

The “don’t waste my mothafucking time” line as well as much of Pacino’s dialogue in this scene is not present in the original script (I checked). “The great ass” line is in the script but I don’t think it was originally intended to be the show stopper it ended up as - even if Mann had Pacino in mind when he wrote it. Such moments are best enjoyed in good company. I had seen the first hour of the film and was more or less ready for “don’t waste my motherfucking time”. But when I revisited the film with my good friend Tyler, neither of were prepared for Pacino’s great “ASS” diatribe, which hit us like the steam roller in Stephen King’s Maximum Overdrive (1986).

Although much of Roma’s ranting and occasionally bizarre dialogue - “you think you’re queer? I’m going to tell you something: we’re all queer” or “You ever take a dump that made you feel like you’d just slept for twelve hours?” - are present in Mamet’s original work written in 1969, the character feels like it was written expressly for the actor that Pacino would become. Still, Pacino’s performance in Glengarry can be distracting and when present in the same scenes, can, like a pungent cologne, overwhelm subtle performances by Jonathan Pryce, Kevin Spacey, Ed Harris, Alan Arkin, and Jack Lemon (one of my favorite actors of all time). Alec Baldwin’s brief but memorable tough-talking performance in the first act, while certainly memorable, pales in comparison to the blaring heights Pacino will reach later in the story.

https://variety.com/1997/film/reviews/the-devil-s-advocate-1117339860/

At one point in the tirade, Pacino tells the people - at a school - that “IF I WERE HALF THE MAN I WAS FIVE YEARS AGO I’D TAKE A FLAMETHROWER TO THIS PLACE”.

https://www.nytimes.com/1992/12/23/movies/review-film-scent-of-a-woman-al-pacino-indulging-a-lust-for-life.html

Speaking of bizarre projects, in his ridiculously feverish but strangely boring JFK (1991) movie, which stars Kevin Costner, Oliver Stone insinuates, among other things, that a “Gay Mafia” was behind the Kennedy assassination. Audiences loved Kennedy, but the Gay Mafia put out the hit, ordered by a miscast Tommy Lee Jones wearing an unfortunate, Travoltaesque hairpiece made for a 60 year old black gentleman.

The thrill-seeking Judge Rayford, a reoccurring comic relief character - is introduced in the film by firing a gun in the courtroom. We later see him during a recess sitting on a ledge outside of his 4th floor office window. On their day off, Rayford takes a terrified Arthur Kirkland (Al Pacino) on a joyride in his helicopter, which, due to the former’s carelessness, runs out of fuel midair, nearly killing them both. Before the film’s courtroom denouement, obligatory in any legal drama, we see Judge Rayford alone in his bathroom with a shotgun in his mouth before being called in to preside over the trial.

The justice system as portrayed in this film is reminiscent of type of caricature we see in Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1972), a broken, politicized machine functioning almost exactly contrary to its intended purpose: protecting the guilty from punishment, especially those with power and influence, while failing to protect and even victimizing the innocent.

George Bluth Sr. in Ron Howard’s Arrested Development.

Hyman Roth in Godfather II.

Junior in The Sopranos. He also played shortstop for the Mets.

Moreover, I would argue that this type of innovative development often flows naturally from the creative process itself. “Must it be?”, muses Ludwig van Beethoven in the top margins of a composition, “it must be!”, he concludes below.

Cruising proved to be extremely controversial and not only among pearl-clutching social conservatives. For example, many critics object to the way the gay community is depicted, describing the film as insensitive and even hurtful. While I do agree that it can come off as dated, I disagree with critic Pierce Baugh’s opinion, which encapsulates this strain of criticism, that “Cruising has no interest in trying to paint gay people in an authentic or empathetic light. They’re disposable. They’re deplorable”. But if they’re ‘disposable’ and ‘deplorable’, then why does Pacino’s character go through so much effort - to the point where it destroys its personal life - to catch this silent killer? Remember that while the killer is a gay man, so are his victims, while also making it abundantly clear that the tragedy of their deaths goes beyond any kind of gay-straight dichotomy.

And while the image Friedkin presents us of this ‘seedy underbelly’ is clearly a perverse depiction, at no point does Friedkin say that anyone deserves to die because of it. If anything, Cruising is a film about the dangers of indifference, the very indifference that would characterize the official lack of response to the crisis due to the belief that it was “a gay disease”, further exacerbated by the mean-spirited cackling of the religious right. When Cruising presents us with this kind of indifference - among the police and public officials, who do not take the threat as seriously as they should - it is anything but a proscription. When two beat cops outside of a gay club hiss contemptibly that “they’re a bunch of scumbags” and heckle passersby, Baugh seems to count this against the movie, but their behavior is obviously not meant to be taken at face value. Actually, the audience is supposed to be disgusted by it - further implying that the ‘gay scene’ we as the viewer are seeing from the outside is not only misunderstood, but also the subject of rampant mistreatment, abuse, and victimization.

In the early 80s, you would be hard pressed to find a mainstream filmmaker both sympathetic to feel this way and ballsy enough to put it on film.