Forward:

The following was originally meant to serve as an introduction of a much longer piece on Vauban, the French mastermind of fortifications and defensive geometry. Military architect, engineer, siege specialist, architect, urban planner, economist, soldier, humanitarian, scientist, and artist; Vauban was a fascinating mélange of all of these things, despite the seemingly blaring contradictions involved in playing (and excelling in) all of these roles simultaneously.

However, in beginning my treatment on the subject with a ‘brief’ history of fortifications, I soon found that what was intended to be a piece of exposition quickly spiraled far beyond what I had planned. Exposition, mind you, is very important - history matters, perhaps more than anything else - but when writing in a blog format, one must be aware of the scale.

“When is he gonna to start talking about Vauban?”, says the ever-present but sometimes reasonable critic in my mind, even if the historically-minded may forgive me for getting carried away. But I am obviously not Robert Caro. If I were to write a Substack piece on Lyndon Johnson, I would certainly not presume to begin the narrative with a hundred-page description of the history, geography, and landscape of Central Texas.

In other words, the result of this ‘introduction’ was a self-contained narrative that could suffice as an article in and of itself. I was hesitant to remove it because of the time and effort I had invested, though I was also aware of the fact that it was simply too large to stay in its original place. So I have decided to release it separately so that it may be read on its own terms.

However, the two subjects are so closely related. I would also encourage the reader - if interested in reading the multi-part Vauban Forts, which will be uploaded shortly - to think of it as an introduction of sorts, though a purely optional one that in no way is compulsory for the full experience.

- MK

The Decline and Fall of Static Fortifications:

“Fixed fortifications are a monument to the stupidity of man”, so goes the famous saying by General George Patton1, the legendary, slightly eccentric commander of American armored forced in the European Theater of the Second World War. Patton was hardly unusual, at least in this respect, among a generation of officers who had learned the lessons of the First and Second World War the hard way.

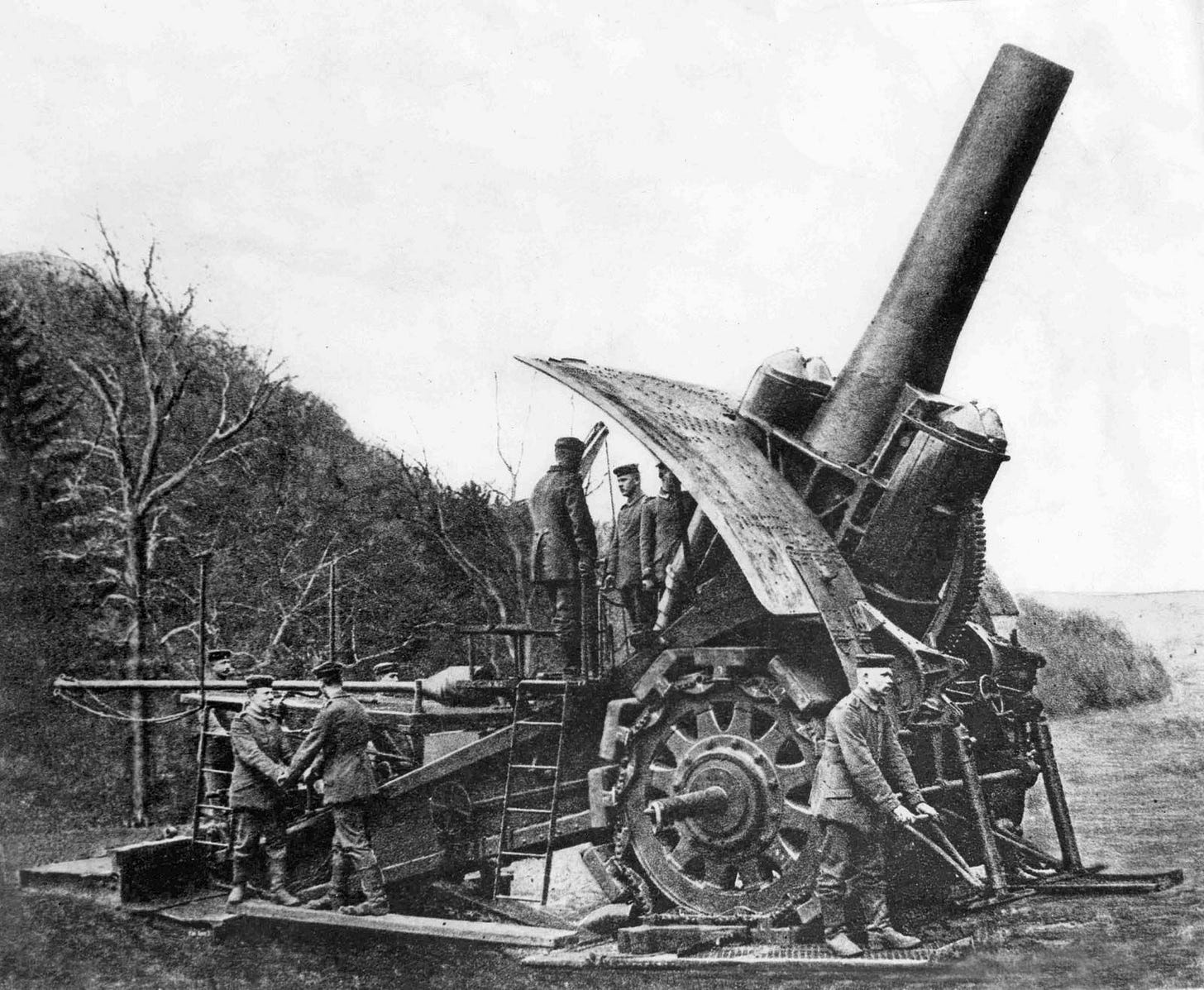

At the very outset of World War I in Early August, 1914, the Germans under General Erich Luddendorf, armed with their ‘Big-Bertha’ 17-inch cannons, made quick work of the Belgian fortress city of Liège, reducing it’s once formidable defenses to rubble in less than forty hours. Compare this to any given Pre or Early Modern siege, which could last weeks, months, even years.

Later in the War, during the nearly ten-month long Battle of Verdun in 1916, the French army only managed to hold the “Région Fortifiée de Verdun” by redeploying massive numbers of men and throwing them against the German onslaught, sustaining horrific casualties numbering up to 400,000.

![r/HistoryPorn - Aerial photo of Fort Douaumont before and After the Battle of Verdun ( 21 February-18 December 1916). This battle was the largest and longest battle of the Great War on the Western Front between German and French armies. [378x570] r/HistoryPorn - Aerial photo of Fort Douaumont before and After the Battle of Verdun ( 21 February-18 December 1916). This battle was the largest and longest battle of the Great War on the Western Front between German and French armies. [378x570]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4ynj!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F78966e81-8fc1-4a51-b1fb-9c5a8906e47e_378x570.jpeg)

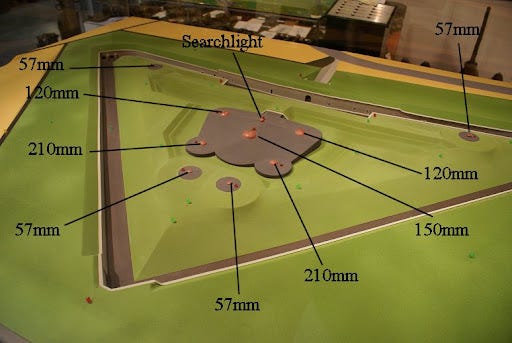

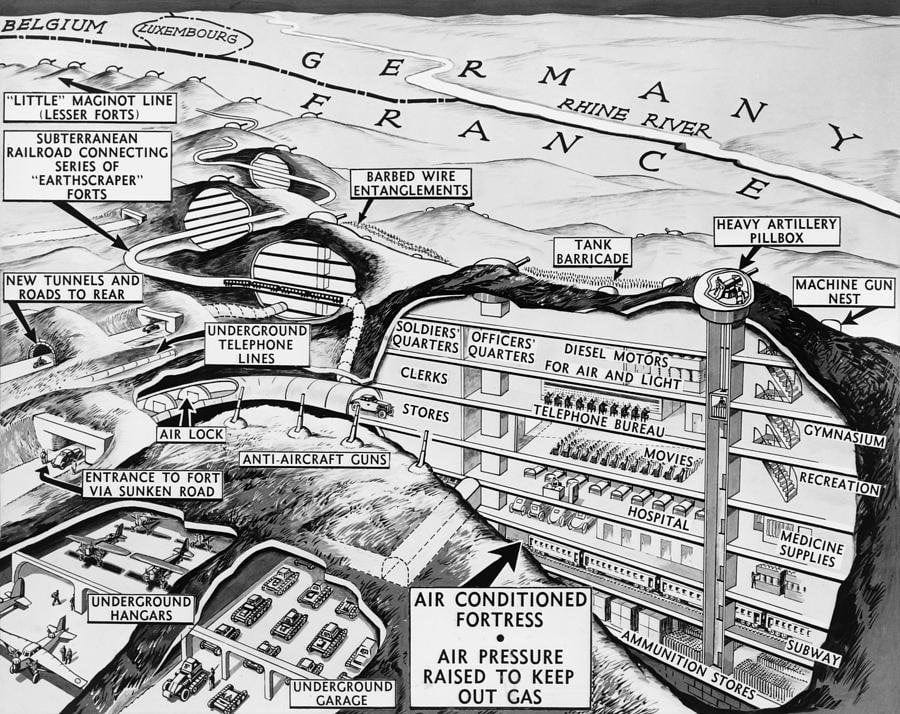

But by far the most infamous example came in the form of The Maginot Line2, a 280 mile long system of forts, bunkers, high caliber gun emplacements, minefields, and machine gun nests connected by an underground railway network and elevators with built-in support facilities to support its defenders indefinitely.

But when war broke out again and the Germans came around to invading France in 1940, instead of facing the Maginot line directly, General Heinz Guderian simply went around it - enabled by the speed that mechanization allowed and highly innovative Blitzkrieg (lightning-war) tactics - and caught the allies completely off-guard, resulting a complete rout in which the French army was completely destroyed, while the British Expeditionary Force, though badly beaten, managed to quit the continent at Dunkirk and return to England.

All of the aforementioned examples represent, what was, for their time, the pinnacle of military science. And so to strategists such as Patton, the reason for their failure was not an engineering nor a technology problem, but rather a more fundamental problem of doctrine.

In fact, by the end of World War II, a war defined in large part by aerial strategic bombardment, it had become clear to most strategists that concentrating one’s entire defense in fixed, not to mention very visible structures had not only lost its strategic value, but had become a terrible idea.

In regard to German attempts to fortify the Atlantic Coast of Europe to prevent allied invasion, the so-called “Atlantic Wall” of fortified pillboxes, bunkers, emplacements, and U-Boat pens, President Roosevelt said boldly, but not inaccurately, that “Hitler built a fortress around Europe, but he forgot to put a roof over it”.

By the war’s end, the allies had developed a 4,500 pound rocket-assisted bomb, nicknamed the “Disney Swish”3, which, traveling at a speed of could penetrate 4.9 meters (16 feet!) of solid reinforced concrete. And this was, mind you, before the massive payload actually detonated. Meanwhile, the British 22,000 pound “Grand Slam” bunker-busting bomb, also developed by Vickers, could penetrate 40 meters (131 feet) of earth to destroy even the deepest enemy strongholds.

Nor could the concrete battlements of “Festung Europa” protect Germany’s cities and industrial capacity from being flattened by the British Royal Air Force and the U.S. Army Air Force and their relentless strategic campaign of Strategic Bombing. One of the most important implications of the war from a tactical/strategic perspective was not only that virtually any static fortification can be destroyed, but rather that instead of facing stationary fortifications head on (i.e. on the defender’s terms) technology can enable military forces to simply drive around or fly over them in favor of easier targets in more favorable conditions - especially to damage enemy’s logistical and industrial capacity, which, after all, is the real target of modern warfare.

Static Fortifications and Explosions in Military History:

When considering the military history of the past five-hundred years, one may observe the following trend: each innovation contributing to destructive power and delivery of explosives corresponds likewise with a decline in the strategic relevance and effectiveness of static defensive structures.

Likewise, the aforementioned examples from the First and Second World War were preceded by a century of rapid industrial and technological advancement. Not least affected was the science of chemistry. An explosion is a chemical process, and nitrates - such as Nitroglycerine or its less volatile and more practical younger brother, Dynamite - make fabulous explosions. Explosions bring down walls.

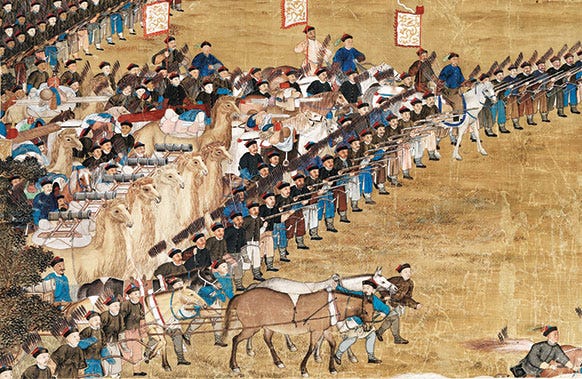

Gunpowder, first developed by the Chinese as early as the Middle Ages, is also a nitrate. It’s introduction from China, to India, to the Middle East, and to Europe in the Early Modern Period revolutionized warfare. And yet even at that time, black powder by itself was not enough. Early Modern cannon could harry a city’s defenses through indirect fire or perhaps create a breach that could then be exploited through infantry, but it could not yet bring down the walls or level an entire city.

Moreover, the use of cannon and firearms in the Early Modern Period was highly impractical, inaccurate, and unreliable. Its use certainly made for an impressive display of power as well as scaring opponents, but its use only became decisive very gradually over the course of the centuries. Thus, much of the history of early modern warfare consists of the trial-and-error process of reconciling the raw potential of gunpowder with its inherent limitations, slowly improved over time by small innovations, both technological and tactical.

A highly illustrative example is to be found in the Siege of Constantinople in 1453 by the Ottoman Turks, lead by their headstrong Sultan, Mehmed the Conquerer. The Sultan commissioned Orban, a Hungarian ironworking engineer to build him a cannon which could “bring down the walls of Babylon itself”.

Although the Basilic, as it was called, could and did cause quite a bit of damage when its 1,200 lb cannonballs actually did hit their target - which was by no means a guarantee - it could only be fired three times a day and needed to be cooled continuously by a steady supply of olive oil. It lasted six weeks before exploding, adding Orban to the long, venerable list of inventors killed by their own invention.

In the end, the Ottoman victory was ensured more by decisive infantry and naval action by anything else, and only after sustaining horrendous casualties at that. And so, for much of human history, even centuries after the widespread adoption of gunpowder, a well-planned fortress would provide its defenders the greatest possible degree of safety. This is because, a would-be besieger, coming upon a formidable fortified position and seeking to conquer it4, would have one of two options:

Attrition: Wait out the siege as the defenders run out of food, water, and other vital supplies while staging periodic, limited infantry attacks and ranged attacks to prod their defenses. This can take months or sometimes years - meanwhile, your own besieging forces also suffer from attrition, with siege camps being especially vulnerable to the ravages of disease, and will become increasingly demoralized the longer it fruitlessly drags on. In situations where the opponents are relatively similar in number, this can be the only leverage the besiegers have, though it is by no means a guarantee of victory. It may seem like the safer option, but it can in fact create an extremely dangerous situation over time. The history of warfare is filled with besiegers who, having been disappointed by their enemy’s resolution and their own lack of success, called it a day and went home.

Assault: Discover or create a weakness or weak point in the defenses and exploit it through a direct infantry assault. The attacker can be reasonably expected to sustain horrific casualties compared to the better positioned, leveraged defenders, who typically will have a much greater motivation to risk their lives than reluctant attackers, who also have nothing to fall behind. A failed assault (which it can be reasonably expected to do), even if it manages to drain the defender’s numbers, leaves the besieger in a far more precarious position. And an army decimated and demoralized is one made especially vulnerable to counterattack, either in the form of the defenders staging a sortie from the safety of their fortifications, or an outside army coming from someplace else to lift the siege. Not few times has such a situation led to the rout and destruction of a besieging army.

Conclusion:

If you visit a modern military installation today, such as an armory or an air base, you will find that beyond a chain link fence there is little in the way of earthworks, bastions, parapets, or towers beyond decoration. To do so in the modern age of warfare would be a patent act of absurdity.

Yet just because things are the way they are now, does not mean that they were always that way, or even have to be that way. For the vast majority of human history, people build castles not for decoration - such as Belvedere Castle in Central Park - but because they worked.

Static fortifications ceased to ‘work’ in the First and Second World Wars because of a series of relatively recent scientific and technological developments (accompanied by doctrinal developments) that expanded the destructive power of the besieging force before finally allowing it to bypass it entirely by driving around or flying over.

Thus static fortifications could no longer do what they were build to do - to protect, rendering even the most advanced and modern castles relics of bygone age, the immense but pathetic, scattered, sun-bleached bones of an extinct species of megafauna, hunted to extinction by a rapacious, constantly evolving, but ever destructive humanity.

Yet as we will see with Vauban, before these scientific developments, the concept itself was not irreconcilable with modern ways of thinking, neither irrational nor unscientific. In fact, Vauban’s Enlightened multidisciplinary approach to their construction - the construction of these '“monuments to the stupidity of man” - may have signaled the advent of modernity itself.

Patton (1888-1945) was known for his eccentricity and volatile disposition. In one infamous example during the Italian campaign in 1943, Patton slapped a shell-shocked Private (i.e. suffering from PTSD) and throwing him out of a field hospital, claiming that there was nothing wrong with him and accusing him of cowardice. This incident effectively ended his career until command, with some hesitation, gave him an army group during the allied invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe. Patton’s most celebrated exploit of the campaign, if not his entire career, was his daring, certainly heroic charge into Belgium in the dead of winter to relieve desperate, freezing, and cut off American division besieged at Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge in late 1944.

In terms of blood and treasure, France had suffered so terribly in the First World War, an estimated 1.7 million dead or 4.3% of its prewar population, that French policy makers in the Interwar Period sought to devise a solution that would simultaneously make the country impossible for the Germans to invade and reduce the long-run cost of maintaining the national defense in a constant state of readiness by reducing strategic dependence on standing armies

The Disney moniker comes from the American wartime propaganda film Victory Through Air Power (1943), animated and produced by Walt Disney Studios in Hollywood, California. It featured, among other things, a seemingly fantastical idea for a rocket-powered bomb dropped by airplane destroying the thick walls of a German U-Boat pen. Allied weapons designers, led by the English inventor Edward Terrel at Vickers-Armstrong, the British arms and aircraft company, were inspired by the idea and built it in real life. Art inspires life, so the saying goes, or was it the other way around?

Assuming of course that negotiation and/or subterfuge are out of the question. Odysseus, of course, famously resorted to the latter option at the Siege of Troy as described in the Iliad.